Erik Thiessen: How Do Babies Learn Language?

How do babies learn language?

Neureality: How would you introduce yourself to our readers?

Erik Thiessen:Hello, my name is Erik Thiessen. I’m a professor of psychology at Carnegie Mellon University. I’ve been employed here since 2004. I got my PhD in Developmental Psychology from the University of Wisconsin, Madison in 2004. And I spent most of my career studying language acquisition in infants and young children.

So the first question is that they’re asking, some babies talk early, others talk late. So what might give rises to this difference? Is it determined by genes? Does baby’s personality play a role?

Excellent question. So this is one of the most notable things about infant language acquisition. That there is a huge amount of variability in the onset of language. Probably the first and most important thing to know about this huge amount of variance is that it is much more pronounced in infancy and early childhood than it’s going to be in adulthood. Well, and indeed, this makes sense. For example, some of those twelve month olds talk and some of those twelve month olds don’t talk. But twelve year olds, almost every one of them talks. So big differences early are going to mostly converge to be small differences later in life.

Another way of thinking about this is specific language impairment (SLI). Specific Language Impairment is a diagnosis that children receive when they are in the slowest ten percent of language acquisition. With no other obvious cause. No physical deformity. No neural deficiency. The deficiency is just language development being slow and we don’t know why. The vast majority of these people with specific language impairment are going to go on and talk normally. So even in this bottom ten percentile of language users, early in childhood, most of these problems and kind of working themselves out. So one of the challenges we face in thinking about the variability in language acquisition is which of these differences that we see in early childhood is going to be persistent differences throughout the lifespan. Some of the early differences are basically just random noise and will wash out over time. But others may continue to show language difficulties throughout childhood and even into adulthood.

We can absolutely say that there is a genetic component to language acquisition. For example, if you are an adult who has a diagnosis of persistent specific language impairment, you are more likely to have a child who is diagnosed with specific language impairment then is a parent who has had no language difficulties diagnosed. We’ve seen this with twin studies we’ve seen that with family tree genetic analysis kinds of studies (e.g., Tosto et al., 2017). There’s definitely genetic component to language acquisition.

Is there a personality component to language can acquisition? Maybe. Personality in infancy doesn’t mean the same thing as personality in adulthood. Infant personality is a much more simplified construct because infants simply can’t express as many behaviors, as many opinions as adults can. So we often refer to personality influence by a different term. We call it temperament. And it’s basically like a simplified version of personality that has two dimensions. Are you happy or surly? And do you respond with curiosity to change, or do you react negatively to change? This temperament matrix, it turns out, does predict language acquisition to a little bit. The children who are more outgoing, more resilient in the face of social challenge are going to reach language milestones a bit sooner, all things being equal.

But probably the biggest thing that we haven’t talked about that makes a difference in language acquisition is linguistic input. How much language are you hearing? And more importantly, what contexts are you hearing that language in? So the very same sentence, for example, can be really informative if it’s a sentence where your parent is talking to you and the parent is really making an effort to communicate with you. In contrast, same sentence could be much less informative to a baby if now that sentence is spoken between two adults to each other rather than between adult to the baby. Because when the adult is talking to the baby, the adult is working to make sure that the two of them are focused are attending to the same objects of the environment. Whereas when two adults are talking to each other, the baby could be attending to anything and the adults are making really no effort to make sure that the baby is focused on what the topic of conversation is. So it’s much easier to learn from a setting in which someone is really focused on you and trying to talk about the things that you’re attending to than a setting in which people are talking. But without being explicitly focused on u as an infant trying to learn.

So is that just simply due to that when we talk to infants we are using infant directed speech?

Infant directed speech does matter. And infants will learn more from overheard infant directed speech, then overheard adult directed speech. But infant directed speech isn’t the only thing that matters. Again, what really seems to be critical here is that when they are talking to an infant, they respond to the things that an infant does. So the infant is looking out of the world and there are hundreds or thousands of objects in the world. What do those hundreds or thousands of things to the mom or dad talk about? Well, they talk about the ones the babies are looking at.

So if a baby is looking at a ball, the parent is much more likely to talk about the ball. So the parent is responding to what the child is focused on. And that makes the linguistic input really better suited to be a signal that you can learn from.

Is that related to join the attention or something?

This is exactly joint attention that we’re talking about. And the thing about joint attention is that an adult we negotiate you’re like, well Erik, you wanna talk about that blue thing. I wanna talk about this red thing. We sort of work it out amongst each other. Which of these things we’re going to talk about. You know, I make a bid to talk about this. You make a bid to talk about that. We go around in circles, we figure it out, we negotiate with each other which of these things we’re going to talk about. Infants and adults are not negotiating in the same kind of way. Instead, in a really high quality linguistic environment, the infant is demanding, and the parent is providing; the infant looks at something, the infant points at something, the infant does something, and the parent responds to this. Now, this is really important. Because when we adults negotiate, we can shift attention. You wanna talk about the red thing. I want to talk about the blue thing. And if you convince me to talk about the red thing, I can shift my attention away from the blue thing and focus on the red thing. I can do that as a little I can control what I want to attend to.

Infants don’t have that same ability to control the focus of their own attention. So if the infant thinks: “ I want to look at the red thing.” and they also heard me saying: “ let’s talk about the blue thing.” The infant doesn’t have the ability to shift their attention away from the red thing to the blue thing. So as an adult, if you want to teach the babies about something that they’re not focused on, you’ve got to work really hard to get them focused on that thing. By contrast, if you want to teach the baby something they are already focused on it, much of your work is already done. So the negotiation process with adults is really hard to accomplish it with infants. As a result, adults seem to adapt to this by basically talking about whatever the infant is looking at.

And so it’s almost like baby, they are so weak in attention control that they need adults not to “bully” on them.

That’s right.

Cool. So maybe we can go to next question. Is it possible that infants they can understand the language and also have an inner speech, but they just can’t express through language?

So the first thing to say is it is not just possible but it’s absolutely true that infants can understand language, can comprehend language before they can produce language. One of the ways that we know this is due to the fact the you know, a few minutes ago, I said, oh, you know, a bunch of twelve month old babies, twelve month old babies are all producing their first word. Well, that’s mostly true. First word on average appears around twelve months of age. But if you take the exact same input to the baby and do it in sign language rather than spoken language. Baby’s first word appears in around six or seven months rather than in a round twelve months. And the reason for this is if I hear you talking and I want to imitate it, I have to do that imitation without being able to see my own mouth. So I can’t just do what your mouth did. By contrast, if you’re using sign language and you hold up for some fingers, I can look at my fingers and make the same communicative gesture.

Does this mean that they have an inner speech and inner mental language? Well, that’s really challenging to know. We can’t do exactly the right kinds of experiments, even in adults. We can’t do these experiments very easily, but in adults, we can at least give people instructions. And we can measure things like reaction time to try to get at what these internal representations look like with infants. Many of these experiments are just not practicable for infants.

That said, what we know is that infants, even preverbal infants show one of the critical abilities that we think about in terms of having a mental life, which is the ability to represent states of the world that don’t exist. Or, to put it another way to say, I want something, and there are a set of actions that I am going to need to take to make something up here to make something happen. So infants are able to do fairly complicated mean-ends tasks. By mean-ends task I mean a task that requires a goal, and babies need to figure out ways to achieve that goal. But of course, you don’t actually give babies a goal. You can’t say to an infant: Your job here is to do this. Instead, you have to take advantage of a goal that they have. Like, they maybe have a goal to put something in their mouth, because babies love putting something in their mouth. And so you put it there and you say the baby. All right, I know you want to put this thing in your mouth. How are you going to do that? And then you give them a situation, a setting where the object cannot simply be reached out and grabbed. But instead there’s some obstacle on the course. Say that the baby needs to navigate, the need to pull on this to make this open up to reach in and grab that thing. And we know the babies are capable of doing that kind of task, suggesting that they are able to represent: “I want this. How do I make that happen now?” Are they expressing these states in terms of well-formed sentences in the English language? No, probably not. So the problem here is not that infants can’t understand the language. The problem is that they can’t produce the language, because they can’t see how their own mouth works. And this takes a long time for them.

How do babies achieve the transition from simply imitating adults speech to actually comprehend the language? So what is the underlying mechanism for this transition? For example, a baby can imitate a lot of words, but it is also quite obvious that the baby has no idea what those words mean. What can parents do to help babies comprehend a language? To go beyond simply imitation.

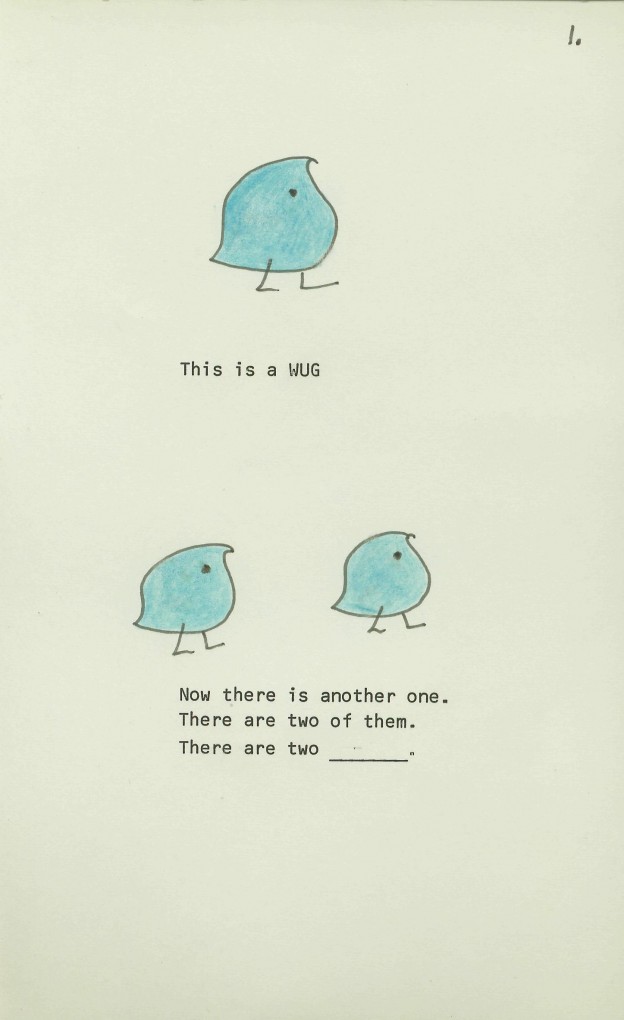

Excellent question. Probably the first thing to note in this space is that even from the very earliest ages at which we can do testing imitation is an important part of language acquisition, but even from the earliest ages, it doesn’t seem to be the only part of language acquisition. A classic example of this was done by the famous development psychologist Roger Brown and a colleague of his named Jean Berko Gleason. They did what’s known as the “Wug task”. In the test, you show a child, a novel object, an object they’ve never seen before, maybe a little doll, maybe a little toy. And you say, this is a wug, then you put up a second one. You say, now there are two of them. Now there are two __?

Wugs?

Exactly. You’ve never heard that word before. So you can’t be imitating; instead, you’re generalizing. You’re taking this pattern that you’ve – learned plural equals add an “s” – and you’re using it in a novel situation. Children do that kind of generalization from a very early age.

But generalization and imitation exist in a kind of constant tension. If you imitate someone, you know that you’re right, or at least you’re pretty confident that you’re right. Now, if you’re imitating someone who speaks badly, then you know you yourself are speaking badly. But generally speaking, imitating other language users is a good idea, because they’re using language correctly. However, imitation is fundamentally limited in that you can only do things you have previously seen done. So generalization is necessary if you’re going to use language and creative ways. But if you generalize too broadly, now you end up using the language incorrectly.

So for example, if I’ve never heard the plural of mouse before, I might say “mouses” when it is supposed to be “mice”. In fact, we see children making these kinds of errors. This is called over regularization. And again, it seems to be part of the story of language acquisition from very early in the process. So children don’t need to learn how to go beyond imitation. They start by trying to go beyond imitation. What they learn seems to be there’s a lot of things happening in language. Some of them you want to imitate precisely some of them you want to imitate kind of closely but not perfectly. And some of them you actually want to ignore. Like when I’m speaking English, I don’t want to speak it in exactly the same way you speak English. I don’t want to mimic your vocal quality or your accent. Those end up being mostly irrelevant. So the challenge for the infant is learning is: “which aspects of language do I want to ignore? Which aspects of language do I want to imitate? Where are things sort of in the middle where I want to do a little bit of imitation coupled with a little bit of generalization?”

How do you help children get better at that process? Well, It’s like any other skill. If I want to learn how to do something, I start by doing that thing over and over again. And then I make it more challenging. So maybe I start by doing learning how to pronounce a letter in exactly the same word position. I’m gonna learn how to say /D/ by putting at the beginning of the word doggy daddy diaper. I just say it at the beginning of the word. Now when I make it more challenging, I put it at the end of the word so the child can see it in different contexts.

This is, we think, one of the critical things in learning how to generalize; first identify something second, see it in lots of different contexts and seeing something in lots of different contexts helps you to identify which aspects of that thing are critical and should always be repeated, or at least attempted to repeat. And which aspects of that thing are more idiosyncratic and can be, you know, abstracted away from or generalized away from.

The next question is about statistical learning. So this person is reading something related to statistical learning last year. And she has a really basic question. There are a lot of evidence for statistical learning, both from behavior studies and neural imaging studies, but she noticed that the monkeys are also found to succeed in statistical learning, but monkeys don’t have human language ability. So even though we can deny the statistical learning plays a role in language opposition this might fail to explain human language system comprehensively. How do currently the researchers in statistical learning view this point? Well, this is a really professional reader.

Yeah, absolutely. For the readers who are maybe a little bit less familiar with the concept, here’s a quick definition of statistical learning. Statistical learning is figuring out units in the environment by detecting which aspects of the input go together. So for example, if you hear the phrase “pretty baby”, how do you know the “pretty” is one word and “baby” is a separate word?. Well, one way that you can figure this out is that when parents speak, they almost always say it to make sure when a baby hears “pre” they hear “ty” coming next in English about ninety five percent of the time. When parents are talking to their children, they don’t say complicated words like predilection or prevaricate or precaution all that often. But at the end of that word “pretty”, many other words can occur next. Yes, you might say pretty baby next, but you might say pretty eyes, pretty shoes, pretty outfit. Sounds within a word predict each other pretty clearly. Sounds at the end of a word don’t predict the next word, because at the end of any word, many, many, many other words can follow. So if you can discover which sounds predict each other, you found sounds that could go together within a word.

So paying attention to how things predict each other could be really important in language. Because of course, language can be described in terms of lots of predictive relationships. When I say “pre” I’m likely to say tty to make the word pretty. When I say “the” I’m likely to have a noun coming because that is part of a phrase that requires a noun. So there’s lots of predictive relations in language. Humans are good at paying attention to this kind of predictive information. And this is what we call statistical learning. And we do think that statistical learning is related to language acquisition. First of all, because of course language has all of these predictive dependencies in it, but second, because individual differences and statistical learning we think are predicting individual differences in language outcome. Those babies who are good at statistical learning are showing faster vocabulary growth. For example, the babies who are less good at statistical learning.

But this reader points out a really good conundrum. Yes, other animals can do statistical learning. Yes, we think statistical learning is really important for language, but other animal species also do statistical learning. And no other animal species developed human language. How do we explain this? One way of explaining this, which I think is sort of implicit in the readers question, is that statistical learning might fail to explain language acquisition comprehensively. That is, statistical learning may be useful for language, but you need some other stuff to get language. So humans have the other stuff. Monkeys and other species only have the statistical learning. So only humans who have statistical learning plus whatever can get all the way to language. And there are lots of theories in this space. So for example, one idea is that to get language, you need statistical learning plus something called theory of mind. The idea that other beings can have different ideas than your own. Because language is fundamentally about communicating ideas. And if you don’t realize that other people have different ideas, communicating ideas isn’t something you’re ever going to be motivated to do. You’re going to assume that everybody else has the same ideas you have. So why should you bother to express those things? So maybe it’s the case that humans are the only animal species to get language, because language requires statistical learning plus something extra on humans. Humans are the only species that has those extra things.

There’s another way of thinking about the problem, which is that statistical learning is a potentially a comprehensive explanation for language. That statistical learning is all you need for language. And the reason that other animal species aren’t getting language isn’t that they lack the crucial learning mechanism. They’ve got statistical learning, and that’s all you need for language from this perspective. The problem is that they’re statistically learning the wrong things. So just a second ago, I said, oh, when you hear “the”, you should hear a noun coming. So that’s sort of true. But I lied about some complexity there, because when I say “the”, a noun is not required to come next, What happens is that when I say “the”, a noun is required to come eventually. I can say “the dog”, but I can also say “the big dog”, “the big fluffy dog”, “the big red fluffy dog”. “The” means that noun will come eventually. It doesn’t mean that a noun is going to come adjacently. Language is full of what we call non-adjacent statistical relations.

Humans seem to be better at detecting non-adjacent regularity. Animals, at least when they’re exposed to linguistic stimuli, seem to be focused on adjacent relationships. And so human statistical learning might work better for language, because humans are naturally interested or able to detect these long-distance relationships, whereas animals perhaps because they’ve got relatively less advanced mental representation capacities, are focused on things that are sort of immediately adjacent. And this makes it more challenging to discover language.

An alternative thing that might be different between humans and other animal species is things that they find interesting. Despite having the very same learning mechanisms, we know that you learn more from things that you find interesting. We also know that almost every animal species on the planet, when given a choice, would rather listen to a member of its own species than a member of another species. And so it might be the case that animals are doing statistical learning just the same way that humans are. But they just don’t pay that much attention to human speech. They don’t detect the same kinds of regularity in the same kind of facility that humans do, because humans find speech way more interesting.

So really, there’s a fundamental divide here. Do animals fail because they don’t have some additional capacity to statistical learning? Or do animals fail because they are using statistical learning, the same capacity humans have, but using it in a different way that humans are using statistical learning. And we still don’t know the answer to this question.

I see. So this is a slightly related question. Is there any lesion study done suggesting that the patients are simply deficient statistical learning?

There has not been extensive work in this space. And what there is has been somewhat contradictory. To start, we need to explain why this has been challenging work to do. If you want to lesion statistical learning, you have to do a lot. Statistical learning is a really widespread neural pattern. I think that it’s at least possible that almost all of the cells in the human brain are capable of doing something that looks like statistical learning. That is a really distributed learning system. But the hippocampus, a structure in the midbrain, really important for memory, does seem to play a pretty important role in statistical learning. And if you lesion the hippocampus, there have been reports of deficits and statistical learning.

Now, again, this is controversial. Some groups find these deficits of statistical learning with hippocampal lesions. Other groups don’t replicate these deficits. You can’t really do the experiment because you need your hippocampus to make memories and no one can volunteer to get their hippocampus cut. So you’re only working with people who have had natural damage to their hippocampus, and each individual patient is going to present with different damage as a function of how their hippocampus became damaged, as well as individual differences in hippocampal architecture that preexisted the damage. But on the basis of this research, what we can at minimum say is that statistical learning is pretty robust to lesion. Even when you lesion the hippocampus and show deficits in statistical learning, these people are still able to show statistical learning in some domains, in some tasks. So again, we think the statistical learning is pretty widespread, decentralized process.

So the next question circles back to babies learning language. This reader wants to know how young children discriminate between dialects. So some adults, they can switch between dialects and mandarin. So mandarine in china is regarded as dialect-free language. But others seem to be incapable of finding a boundary between the two. Is it due to different family environment in childhood?

Challenging question to answer. There are major differences in this space between adults. Some adults who acquire a second language or a second dialect seem to produce all of their dialects for all of their languages really fluently in in a way that is accent free. Other people acquire a second or a third or fourth language. And even though they can speak the language perfectly well, they continue to have an accent. They continue to show dialectical patterns. And we don’t have a great sense of why one adult would be accented as a speaker, and one adult would be accent free in their ability to learn language. Age of acquisition does seem to have something to do with it. The younger you learn your language, the more likely you are to produce it like a native speaker, rather than producing like an accented foreign speaker.

We do think that there are individual differences in this space as well, potentially genetically motivates individual differences. Some children just might be better at learning to control their articulators, the mouth, the jaw, the tongue, the lips, and producing things in ways that sound like native speakers produce them. But what we can say for sure is that young infants find this challenge a little easier than older children and adults. Children are able to perceive a pretty wide variety of speech sounds that any language in the world is going to want to use. By the time you’re about a year old, you spent enough time listening to your native language that you primarily perceive sounds that the native language wants to use. And you ignore sounds that the native language doesn’t want. So for example, English uses the “r” “l” “ra” “la” distinction. Japanese doesn’t use the r/l distinction. At birth, both English learning and Japanese learning infants can perceive the /r/-/l/ distinction. By twelve months of age. Japanese learning infants have lost the ability to perceive the distinction, because it’s not useful in their language.

So the longer you spend immersed in language one, the better you get at language one, the more you’re going to be biased when you get exposed to language two. You will try to interpret it in terms of what you know about language one. And if you already know language one pretty well, it is really easy to interpret language to in terms of language one. And so if you’ve already picked up one dialect, it’s pretty easy to try to map your new language onto that dialect. Whereas if you’re learning both languages at the same time, one of them doesn’t have an advantage over the other one doesn’t become dominant. And so you can learn them both relatively independently. This probably makes it easier to switch back and forth between them using native like or on accent and speech patterns.

So in terms of accent, how do people actually measure it?

It’s challenging work to do because you can’t a priori specify what an accent is or isn’t going to sound like. You need to really immerse yourself in the language community. You need to get trained raters who know what kind of sound speakers in the light of native community produce and then you can tell speech raters to rate it as being super native like or not super native like. Actually one of the most reliable ways to do this is just give samples of language to people who speak a language and asked them to rate it. How much does this sound like one of you folks said this, or how much does it sound like somebody who’s from not from around here.

Interesting. So the next question is infant language acquisition and mirror neuron. Is that related?

Well, we don’t know. So again, for those readers at home who are maybe have immersed themselves in this literature, a mirror neuron is a neuron that seems to fire or respond in exactly the same way when you are doing an action and when you are watching someone else do an action. This might be really useful for language, because of course, language necessarily require some imitation – or consensus – between speakers. You have an idea in your head, and you want to convey that idea to someone else. And a mirror neuron might provide a natural translation mechanism, if you will. For I have an idea in my head. Oh, I can see that you have the same idea in your head. That could be what mirror neurons are for allowing us to say: This idea in here is the same as it is out there in someone else.

However, there is not yet a literature, to my knowledge, that says children who have more mirror neurons are better at learning language. Children who don’t have mirror neurons don’t learn language. There’s not much of a literature yet linking the activity or the actions of mirror neurons to language learning outcomes.

So at present, I think we say mirror neurons could be related to language acquisition. We’re making a plausible but speculative claims.

So is most of like the literature of mirror neurons are about like actual like real movement you made with your limbs or hands?

Yes, exactly.

And if you really, really want to push like that language, it is almost like you need to observe how their mouths are moving.

And that would be one way to get the job done for sure. One of the things that help us learn how to imitate vocal apparatus, because we can see your mouth moving. And I know that my mouth is moving in exactly the same way. It’s a plausible link. But again, to my knowledge, we haven’t really done the neural imaging or the behavioral work necessary to substantiate the claim.

Cool. So the next one is also related. So how does infant detect the emotional language? Can we make the claim that early stage of language acquisition is a form of acquisition of emotion, expression?

Good question. First, how does the infant detect emotion in language? I think most people in my field think that this is not something that infants learn to do, but rather that it is something that comes basically hard wired out of the auditory system. Now, to give you an example of why this might be think about talking with an animal that doesn’t understand human speech.

When you wanna tell your dog that they’ve been a good dog, you probably say something like “good dog~”. You probably don’t YELL good dog! I love you! Dog! My dog!

We tried this on my dog. It terrifies him.

Yeah, exactly. It seems to be the case that sort of across the mammalian auditory systems in the world, things that are low and slow are soothing. Things that are sharp and high pitched are startling. And things that are loud and abrupt are warning signals. We think that infants get this for free. We think that this just falls out of the way the mammalian systems have evolved their ears over millennia. So infants don’t need to learn to interpret emotion. They pop out into the world predisposed to when they hear low and slow, like, oh, good, cool. Everything is fine. When they hear fast and high pitched, they’re thinking, oh, I’m startled. This just falls out of the way the ear works.

However, the other part of the question is can we make the claim that early language acquisition is a form of the acquisition of emotion expression. Emotion comprehension seems to come for free. Expression maybe doesn’t come for free. And one way of thinking about this is that when children are little, very, very little, they don’t do a very good job expressing their emotions. They’ve basically got two states. I’m upset and I’m fine. And that upset covers a lot of space. They could be upset because they’re hungry, because they’re irritable, because they need to be changed. Gosh, it covers a lot of space. So the ability of the infant to express emotion, I think does become more refined over the course of development, perhaps because they start out with the ability to comprehend emotional signals pretty well, they can eventually learn to imitate those emotional signals in their own production systems.

So back to the previous like this hardwired emotion detecting ability. I’m thinking is this universal across species?

It does seem to be pretty universal across mammalian auditory systems. I haven’t checked in lizards or birds, but mammals all seem to respond in pretty much the same way to this emotion information in speech.

Now the last question is also a super professional one. This question is about the early first language acquisition in international adoptee. For example, one adoptee has been exposed to Chinese in infancy and then completely forgets how to speak Chinese after being adopted by a French family and living there since. However, when she or him is doing this phonological working memory task, his or her brain area is more similar to Chinese-French bilingual rather than French monolingual. So does early language exposure really leave the so-called trace?

So first of all, the answer does seem to be, yes, early exposure does leave a trace. Maybe this shouldn’t be surprising. Virtually every experience that we have shapes our brain. So, in some sense, it would almost be more surprising if hearing Chinese for a few years early in your life didn’t shape your neural responses. What’s surprising here is that while the brains of these people are more similar to a Chinese bilingual’s than to a French monolingual’s, even though they completely forgotten Chinese. Their brain responds as though they had learned it but they don’t remember ever having heard Chinese. When you put them in a task that has them discriminates tones for example. There are no better than French monolinguals are.

So there’s an early impact on the brain, but it leads to very minimal, very subtle, if any at all, behavioral changes later in life. Now, there has been some work suggesting that if you are an international adoptee and you heard Chinese for the first year or two of your life. And then you forgot it. When you, as an adult, try to learn Chinese as a second language, you will have a little bit of an advantage over a true French monolingual who hadn’t spent two years of their life hearing Chinese. So there’s some potential savings, but they’re not big.

So really the challenge in this space is to try to figure out why does the brain adapt in ways that functionally have basically very little effect. Like functionally, it kind of doesn’t matter if you’re a fourteen year old French speaker who spent a year or two of the first part of your life listening to Chinese, or if you’re a fourteen year old French speaker who’s never heard Chinese. Those two fourteen year olds are both going to be French native speakers. One of them has a little bit of Chinese hanging around in their brain. Why doesn’t it have a behavioral effect? When does it occasionally have a little behavioral effect? Those are the questions we’re trying to answer in this space.

评论